So here we are, a couple of days from the launch of Plague of Swords, and you’d probably expect me to blog about writing either Plague of Swords or Fall of Dragons. But, dear reader, I like to surprise; I also think that many of you like to have a little window on the life of a writer.

So here goes. My next series, at least for fantasy, is called Masters and Mages. (In my head, it’s just called ‘Mastery’ but there you go). Some of the content of book one, (The Master) has wandered around the net; I tried some of it as freeware, and then I sold it to the nice folks at Gollancz. It’s a completely different world; there’s neither a Christianity nor an analog thereof; I made up all the religions; and it has a new magic system (actually a number of different magic systems.). There is a lot of swordplay; but this time, there will be analog Chinese and Japanese and Persian and Turkish swordplay to go alongside the analog Italian and German and English.

You will find similarities…after all, this is still me…

Now, you might ask, what on earth does this have to do with calligraphy?

Well, about four months ago, I started to be fascinated by medieval books of hours (who isn’t, really). I wasn’t just fascinated by the awesome penmanship and the glorious illustrations.

I was fascinated by the amount of effort; the very practice of all these arts together, just to make a book, and how precious that book must have been. Paper appears, commercially, in Europe in about 1300 (give or take) and even after it appears, was still ‘lesser’ to vellum, which is sheep (or goat) and the very devil to prepare. Of course, well prepared vellum is pretty much eternal; unlike, say, the terabyte hard drive holding my daughter’s entire youth in pictures and which will decay to uselessness in another 5 years. Or like most of the books I own, on acidic paper… but I digress.

The more I examined pre-modern books, the more I decided that I needed to make one, to understand the process; I needed to learn some basic calligraphy. (If you want to understand how to make a medieval book, start here.) Hey, it’s not all sword fighting; I like to dance and cook, too. So, with help from friends, I got some equipment, and I started on Gothic Quadrata, a scholarly hand of the fourteenth century.

It’s really fun.

Who even knew? I’ve got about twenty days in this little micro-passion so far, and I now own pens and papers and I’m delighted and amazed at the excellent advice I’ve received on facebook (and a formal thanks to Jason Daub, Jiliyan Milne, David Harden and Cliff Mullin. Also a sort of delighted puzzlement at how many of my friends already do this… why didn’t anyone tell me?)

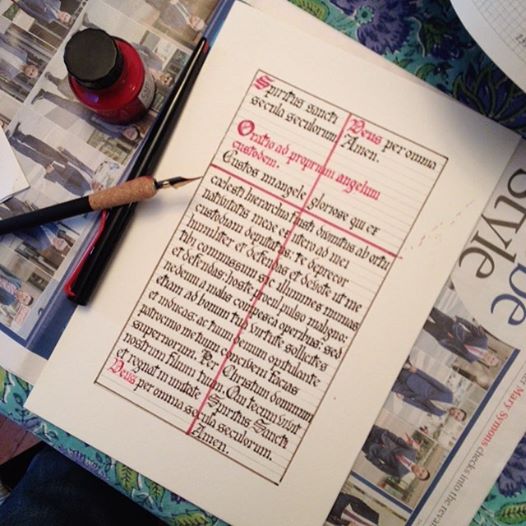

The above is riddled with errors. But it also marks the beginning of the project; I’m writing a whole book of hours. These will be the back pages; I figure that when I get to the front folios, I’ll be much better at the calligraphy and the illumination. I plan to ask my friend the artist Aurora Simmons to give me a couple of actual miniature paintings (the annunciation of the Virgin is a standard; maybe a Crucifixion, or maybe a Saint Michael).

This is, after all, my favorite medieval illustration of all time; the very model for the Red Knight… the deep inspiration… Also, for the harness I wear when I fight. Also for a certain amount of contemplation.

And the more time I spend on this, the better I get. No surprise there. ‘Practice’ is pretty much my battle cry.

This is my latest effort. I admit, I’m quite proud of it, although I can see many errors; my ‘t’s are weak and my ‘m’s and ‘n’s are still not even and I do tend to cramp my hand.

All true. But here’s the point about ‘The Master.’ In just twenty days of doing this calligraphy, I’ve learned an incredible wealth of detail about being a scholar in the pre-modern world. My young hero/protagonist is going to university, where, I freely confess, he’s more interested in girls and swords than in his studies. But calligraphy has given me some insight into the issues facing a scholar, even in a magical alternative reality; a world in which, to own a book and study it, as a poor student, you pretty much need to copy it out yourself; how the process of copying can educate you; how fatiguing it might be; how working in a tannery could give you a leg up as a writer (cheaper vellum) and make you smell all day of dog shit (oh, yeah).

My new world isn’t in the late fourteenth century of ours; it’s even more complex, and there may, just may, be an airship or two, and the technology is a little more like the late sixteenth century in some places. But one thing no one has yet is the printing press. Scholars copy books.

And now I know a lot more about that experience. At least the western experience; and I will be reading about Chinese and Japanese calligraphy in coming weeks, while I write the last pages of ‘Fall of Dragons’ and bid goodbye to the world of Alba and the Red Knight. that is the reality of being a working writer; you have to look ahead, research ahead, and read about one thing (and be passionate about it!) while writing about another.

Wish me luck.

Impressive to say the least, all you have achieved. And I’m super excited about your new venture and world, from the hints you’ve given. Good luck, Christian. Although it’s your passion and hard work more than luck, methinks.

LikeLike

You are way too nice to me 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on J P Ashman and commented:

Fascinating to say the least. History fan, or fantasy fan? Then check this blog post out from author Christian (Miles) Cameron.

LikeLike

As you say you really learn by doing/experiencing…

Good luck.. look forward to the next adventure…

JW

LikeLiked by 1 person

Two points you might want to think about.

According to one recent scholar, it is quite inaccurate to think of the marginal illustrations of medieval books as light-hearted contributions of the scribe. It would have been the patron who commissioned the book who determined what went into the book. Think of the long meetings and the arguments (perhaps somewhat restrained on the part of the scribe/artist) that took place before the final decisions on content were made!

Also, copies were so expensive that few copies were made of most works. Think of Matthew Paris. People who wanted access to his information and commentary of recent history had to go to him in St. Albans. The monastery there was of course rich and important, but his chronicle (and earlier ones at St. Albans) must have been an important element in its institutional reputation.

Finally, how big a workshop did Froissart support, and where did he get the capital to get it off the ground? He didn’t have a life-long connection to a centuries-old monastery!

LikeLike

I love this. I used to do Calligraphy myself. Then I broke my hand now I can hardly hold a pen, but I still love looking at it .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely! That does look like a lot of fun. I hope you have as much fun writing the new series. Good luck!

LikeLiked by 1 person